Recently I’ve been working my way through the Apocrypha. If you aren’t familiar with these, they are a collection of Jewish writings composed during the time between the Old and New Testaments (400 BC to the first century AD).

The term “apocrypha” means “stored away,” from the Greek word for “hidden.” The early church father Origen, for example, used it to refer to books that were to be kept out of public reading in church liturgies. But which books counted as “apocryphal” was something that changed over time and depended on who you asked.

And it wasn’t based on conspiracies or anything, as if these books were forbidden. They were still read by Christians. But it was often disputed whether they were to be considered divinely inspired and authoritative. On the one hand, you have such theological giants as Augustine of Hippo arguing strongly for their canonicity. On the other, you have some equally respectable figures like Origen, Cyril of Jerusalem, Athanasius, and especially Jerome excluding them from the canon, particularly on the basis that the Jewish people had also excluded them.

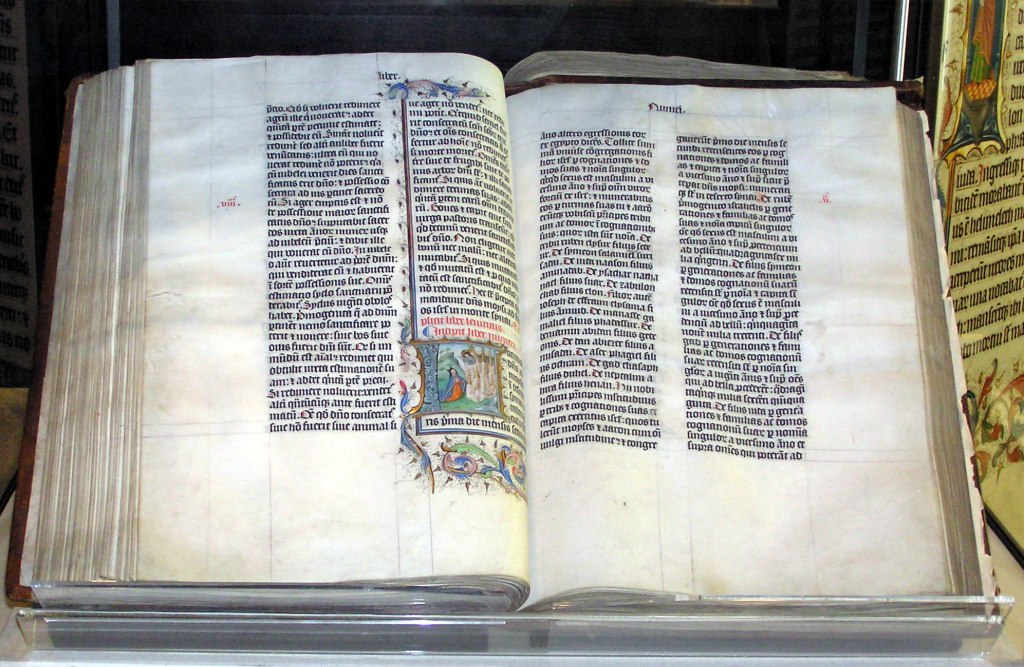

The tricky part is that no ecumenical council of the early church ever definitively settled on a list of the biblical canon. This meant that what could be read liturgically in church as Scripture varied by regional custom, all the way into the days of the Protestant Reformation in the 1500s, when battle lines became more sharply drawn on the Apocrypha.

Most Protestant Christians land on a negative answer to the question of the Apocrypha’s inspiration, and so we do not view them as equal to the canonical books of Scripture but might still read them for their historical value. A lot of modern English Bible translations have stopped including the Apocrypha (originally to save money on printing!), but you can find them in some editions of the KJV, the NRSV, the ESV, or in Catholic or Orthodox Bibles.

Roman Catholics, on the other hand, consider the Apocrypha canonical. The Catholic Council of Trent in 1546 firmly decided to make the Apocrypha canonical for Roman Catholics, specifically in response to the Protestant conclusion. Many Eastern Orthodox Christians also affirm the Apocrypha, although their canon lists vary by region.

In the Anglican tradition, we hold to the view well-summarized by the church father Jerome: that the Apocrypha ought to be read for our instruction and for example, but we do not establish doctrine from them. In other words, broadly speaking, Anglican Christians seek to maintain a respect for the value of the Apocrypha as historical and devotional literature, and as witnesses to the continued faith of Israel between the Testaments, while also acknowledging the doubts which many church fathers expressed about their inspiration. The Anglican communion is one of the only groups within Protestantism that continues to include selections from the Apocrypha in our lectionaries, liturgy, and hymnody.

So what are the apocryphal books, and what are they about? Here’s a quick overview of each one, for your convenience!

Tobit: A short story/folk tale about a pious Jew named Tobit living in exile in Assyria. When Tobit falls ill with blindness, he sends his son Tobias to settle a debt with a distant relative. Tobias is unknowingly accompanied by the archangel Raphael in disguise, who leads him on a quest to save the pious maiden Sarah from the demon Asmodeus. Tobias succeeds and marries Sarah, settles his father’s debt, and returns home, where Raphael reveals himself and Tobit pronounces a blessing on his children before passing away in peace. Likely composed sometime between 300 and 175 BC, Tobit seems to have been written both to entertain readers and to inspire respect for traditional Jewish values in the midst of life in exile: family, marrying within the covenant race, respecting the dead, and especially almsgiving. The book’s emphasis on giving alms as a way of ensuring blessing for oneself is paralleled in Dan 4:27, and later echoed in Sirach, the NT (Luke 12:33-34; Acts 10:4; 1 Tim 6:18-19), and early Christian literature like the Didache, the Shepherd of Hermas, and the Epistle of Barnabas. Tobit also displays developments in Jewish angelology in the intertestamental period.

Judith: A short story in which the land of Judah is besieged by Nebuchadnezzar’s army and its commander, Holofernes, but is saved when the pious widow Judith manages to insinuate herself into Holofernes’ company and behead him while his guard is down. The story, which was probably composed sometime after the Maccabean revolt (167-160 BC), is filled with dramatic irony and clever remixes of earlier biblical stories (such as Jael’s defeat of Sisera in Judges 4). The presence of these riffs on other stories, as well as the many anachronisms in the book (like calling Nebuchadnezzar the king of Assyria rather than Babylon), suggest that it was meant to be read as a historical fiction or parable, perhaps to promote support for the Hasmonean party (the successors of Judas Maccabeus) in Judah against their Gentile enemies. It also promotes the Jewish faith by lampooning the Gentiles (and their gods), who are overthrown in the story by a lowly widow known only for her faithfulness in prayer and her observance of Torah.

Additions to Esther: The Greek translation of Esther found in the Septuagint texts contains several additional chapters not found in the Hebrew text tradition. These expansions do not change the core story much, but instead serve to make the book more explicitly religious through mentions of God and of the Torah. There are also several places where ancient “historical documents” are added into the text to bolster its historicity. Most of these additional scenes appear to have been composed later than the Hebrew version, and may have been motivated by efforts to secure the book of Esther’s canonical status. (There’s also a cool dream sequence where the struggle between Mordecai and Haman is represented by two dueling dragons. So that’s fun.)

Wisdom of Solomon: A theological reflection in the form of a fictional address from King Solomon to the rulers of the Gentile world. “Solomon” exhorts them to submit to God’s wisdom, abandon idolatry, and live righteously, or else they will face punishment at the final judgment. The second half of the book uses the plagues of the exodus as an example of the sovereign God’s ability to punish the wicked with the very things they worship, while delivering the righteous. Scholars generally hold that Wisdom of Solomon was composed in the first century BC in Alexandria, Egypt, which had a substantial Jewish population struggling to live amidst their pagan neighbors. This would explain the book’s denunciation of creature worship and its use of Exodus themes. By presenting itself as the testimony of Solomon from beyond the grave, it also ties itself to Israel’s other wisdom literature, such as the Psalms and Proverbs. Wisdom of Solomon significantly develops the concept of a judgment after death more than the OT did, and its depiction of a personified, heavenly Wisdom would later play a role in the church fathers’ explanations of Christ and the Trinity. Wisdom’s presentation of idolatry and God’s general revelation in nature appears to have had a large influence on Paul’s thought in Romans 1-3.

Sirach (also called Ecclesiasticus, or the Wisdom of Jesus ben Sira): A sequel of sorts to the wisdom literature in the Old Testament, such as Proverbs (which Ben Sira obviously drew heavily from and modeled his work after) and Ecclesiastes. The author of the book was a Jewish sage named Yeshua ben Sira, and the book itself is a compilation and translation of his work into Greek by his grandson. Ben Sira was probably active around 196-175 BC, meaning that his work reflects the period shortly before the Maccabean crisis in Judea. The translation was probably produced between 132-115 BC. Sirach may have served as a curriculum of sorts for Jewish students to learn traditional wisdom rooted in Jewish piety during a time when there was pressure to conform to encroaching Greek culture and values. Many of the ethical teachings in Sirach are echoed in the NT (especially in Matt 6-7 and James 1). However, while much of the advice in Sirach is still quite helpful even today, it does sport a few intensely misogynistic passages (25:13-26; 26:10-12; 42:9-14), which played a role in later Jewish and Christian interpreters downplaying the book’s authority as a sacred writing, or at least seeking to find its worth in its other passages.

Baruch (and The Letter of Jeremiah): This document purports to be an epistle from Baruch (Jeremiah’s scribe and assistant) to the Jewish people living in exile in Babylon. It divides into three parts: the first section (1:1-3:8) reflects on the destruction of Jerusalem and the exile and includes a prayer of confession affirming God’s covenant justice as prophesied in Deut 28-30. The second section (3:9-4:4) is a poem encouraging the Jewish people to seek the wisdom found in God’s Torah. In the final section (4:5-5:9), a personified Jerusalem gives a poetic lament over her people’s exile but predicts their eventual gathering and return from the east. A sixth chapter, often printed separately as The Letter of Jeremiah, is a scathing denunciation of Gentile idolatry, much like what is found in Jer 10:2-15. Both documents display how Jews in the Second Temple period reflected on their experience of exile and subjugation under the Gentiles in light of biblical prophecy.

The Prayer of Azariah & the Song of the Three: The first of three apocryphal Greek additions to the book of Daniel, inserted between Daniel 3:23 and 3:24 (the story of the Hebrew youths being thrown into the fiery furnace). This prayer and the following hymn were probably originally composed as separate liturgical pieces to be used in Jewish temple worship, but were placed into the mouths of the three Hebrew men in the fiery furnace, where they take on added theological significance – affirming God’s justice and glory even in the midst of (literal!) fiery trials. The Song of the Three is still used to this day as a canticle (hymn) in the Anglican daily prayer office.

Susanna: The second addition to Daniel is a short story in which two wicked Jewish elders attempt to trap the beautiful Susanna to have an affair with her, but when she refuses they accuse her of adultery and attempt to have her executed. However, the wise youth Daniel manages to deduce the elders’ trickery and thwart their wicked plot. Susanna has been called the world’s first detective story. Susanna’s decision to obey God even at the risk of her own life continues that central theme of the book of the Daniel, while Daniel’s cleverness highlights the need for discernment even in court cases that seem black-and-white.

Bel and the Dragon: The third addition to Daniel, in which Daniel uses his wisdom to prove the falseness of Babylon’s idols. In the first scene, he refutes the claim that the statue of Bel is able to eat its sacrifices. In the second, he proves that the king’s “dragon” (or large snake) is not immortal when he manages to kill it. And in the final scene, Daniel in the lion’s den is miraculously fed by the prophet Habakkuk.

The Prayer of Manasseh: A psalm of confession and repentance associated with Judah’s king Manasseh (ruled 687-642 BC). While 2 Kings 21 presents Manasseh as the most wicked of all Judah’s kings, whose idolatry eventually sealed the nation’s doom, the version of his story told in 2 Chronicles 33 adds that he eventually repented. The idea of God’s mercy being available to even the most wicked sinner in history is highlighted in this beautiful hymn, which praises the Lord as not only the God of the righteous, but “the God of those who repent.”

1 Maccabees: An account of the Maccabean revolt and the establishment of the Hasmonean dynasty in Jerusalem. When Greek king Antiochus Epiphanes mandates Greek religion and culture in Judah and defiles the Temple, Judas Maccabeus and his brothers wage a guerrilla war for Judean independence and retake Jerusalem. One by one Judas and his brothers give their lives for the cause until the last one standing, Simon, establishes peace and becomes king and high priest of Judah. 1 Maccabees contains many echoes of the OT historical books, indicating that its author believed Simon’s line was providentially given victory in keeping with God’s covenant. It covers the period from 175 BC to around 104 BC, and so was likely written sometime around 100 BC, likely to encourage support of the Hasmonean priestly line. This was in the days of the Greek empire when Alexander the Great’s successors, the Seleucids in Palestine and the Ptolemies in Egypt, were fighting for power, and Rome was flourishing as a republic in the west. Many of these international intrigues play a role in 1 Maccabees.

2 Maccabees: While its title might suggest that this is a sequel to 1 Maccabees, this work was in fact likely written earlier and thus functions more as a prequel. It gives more detail and embellishment to the stories of Antiochus Epiphanes’ assault on Jerusalem and Judas Maccabeus’ liberation efforts (175 to 167 BC). 2 Maccabees is an abbreviation of a longer account that is lost to history, and its author chooses to highlight the sacredness of the Jerusalem Temple and the bravery of those who died as martyrs rather than assimilate to Greek religion. The account of Judas’ purification of the Temple is the historical basis behind the holiday of Hanukkah (or the “Feast of Dedication” – see John 10:22).

The Books of Esdras: What is sometimes referred to as 3 Esdras (but in the NRSV and many other editions is called 1 Esdras) is a retelling of the biblical book of Ezra, but with a few additional scenes (including a famous scene where the Jewish leader Zerubbabel wins a contest of wits in the court of King Darius). The book sometimes called 4 Esdras (but often printed as 2 Esdras) is a composite work, most of which dates to the end of the first century AD (contemporaneous with some of the NT). In it, Ezra receives apocalyptic visions of the end of the world and the arrival of the “Son of Man.” It is essentially a Jewish parallel to the NT book of Revelation, which shares similar themes but identifies the Son of Man as Jesus. Thus 4 Esdras, while written too late to have been a direct influence on the NT, nonetheless serves as an example of the kinds of apocalyptic themes and ideas that were circulating among Jews in the first century AD.